In today’s video streaming world, the terms “live” and “real-time” are used interchangeably, when in reality, they involve two completely different user experiences. “Live” video may have more than 60 seconds of latency or lag, while real-time video is defined to have under 0.5 seconds of latency. The term latency here refers to the amount of time between when video is captured by the publishing device to when it is viewed on the subscribing device. Even the mainstream media confuses this terminology on a regular basis when covering the streaming industry. Forbes wrote an article in March 2016 showcasing this misconstrued notion that live and real-time are identical in a piece titled, “The State And Future Of Live Video and the Rise of Real-Time Creators And Audiences”[1].

Furthermore, CIO.com, an award-winning tech blog that highlights expertise on technology innovation, noted in January 2017, “Livestreamed video took off on social in 2016, and many believe 2017 will be the year it explodes. Prerecorded video will still have its place, of course, but brands will increasingly use real-time video to engage target audiences during the coming months.”[2]

The reason why these discrepancies have not been detailed by the media community is primarily because up until now, real-time video was never scalable to large audiences. “Live” was the only option for companies like Facebook and Twitter to reach hundreds of thousands of concurrent viewers.

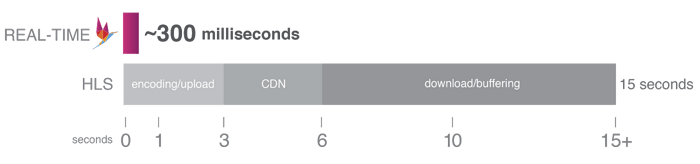

Most large-audience, “live”-streaming providers primarily use an architecture composed of HLS (HTTP Live Streaming) technology coupled with a content delivery network (CDN). This architecture typically has a minimum of 15 seconds and often over 60 seconds of latency, preventing true real-time interactivity and limiting audience engagement. The video latency has a number of input variables, but the processes of chunking video into 2 second segments, sending them over a CDN, and downloading chunks on the viewer’s end device are significant contributors to lag time. These restrictions limit the collaborative environment available to businesses and consumers. HLS has become an industry standard ripe for innovation and real-time connectivity.

Platforms using this HLS/CDN architecture include Livestream, Facebook Live, YouTube Live, and Periscope/Twitter. The New York Times recently documented the shortcomings of Twitter’s streaming capabilities in an article after Twitter broadcasted its first NFL game on September 15th, 2016 stating, “the instantaneous nature of Twitter ran headfirst into the speed-related flaws still inherent in streaming video…as soon as the stream went live, fans noted how delayed the action was compared with the broadcast on CBS.”[3]

The video streaming world is beginning to notice that “If it’s live, it’s too late™”.

Conversely, while real-time solutions on the market have very low latency, most are not scalable past several hundred concurrent viewers. This is primarily because the majority of real-time video streaming platforms are built on top of an open-source WebRTC (“Web Real-Time Communication”) implementation, which was only designed to connect small groups of people. Therefore, use cases for real-time video to date have centered around one-to-one conversations and group chats, as broadcasting to large audiences was simply not an option.

Phenix has broadened the aforementioned use cases dramatically with its proprietary PCast™ real-time video streaming platform. The Phenix team has engineered a new wave of real-time communication capabilities, building its platform from the ground up with the ability to scale to millions of concurrent viewers while maintaining less than 0.5 seconds of end-to-end latency.

[1] Solis, Brian. “The State And Future Of Live Video and the Rise of Real-Time Creators And Audiences.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 29 Mar. 2016. Web. 18 Jan. 2017.

[2] Martin, James A. “What Marketing Pros Need to Know about Live Video in 2017.” CIO.com — Tech News, Analysis, Blogs, Video. CIO, 04 Jan. 2017. Web. 18 Jan. 2017.

[3] Hoffman, Benjamin. “Twitter Live Stream of ‘Thursday Night Football’ Reveals Delay-of-Game Flaw.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 15 Sept. 2016. Web. 19 Jan. 2017.